Five years ago, I wrote about Nassim Taleb’s book, Antifragility. The book built on the ideas developed in Fooled by Randomness and Black Swan. On 26 January 2020, before its outbreak in the West, he wrote a prescient warning about covid-19.

Taleb writes about probability and how humans fail to correctly estimate probabilities, especially the very low probabilities at the tails of non-linear distributions (“fat tails”). People wrongly tend to extrapolate from a normal situation. Taleb coined the terms “black swans” (highly rare and unforeseeable events) and “white swans” (highly rare but foreseeable events) to describe such low-probable but highly consequential events.

Landscapes are mostly the result of extreme events in the past (volcano eruptions, tsunamis, ice ages…), much more than the daily grind of erosion and sedimentation. Similarly, black and white swan events have an outsized influence on our politics, economies and societies.

The concept of antifragility is related to resilience and robustness, but the difference is that antifragile systems become stronger under pressure, like bones or muscles become stronger when they are tested.

The shock of the pandemic has exposed the increased fragility of the western world: tightly integrated global networks and supply chains and a reliance on China for key resources such as pharmaceutical ingredients. This means that risks such as pathogens, computer viruses, cyber attacks or reckless budgetary management by companies and central banks are likely to cause global rather than local shocks.

Africa’s relative exclusion from global supply networks has so far spared it from the worst effects on the pandemic.

Taleb advocates for more antifragility in the system. “That’s why nature gave us two kidneys.” Antifragile systems are characterised by optionality, redundancy and variability. They contain the institutional equivalent of “circuit breakers, fail-safe protocols, and backup systems.

Some elements of such antifragile systems are:

- distribution of power among smaller, more local, experimental, and self-sufficient entities

- no monopolies or centralized bureaucracies (against increasing trends towards winner-takes-all markets and data centralisation)

- public but decentralized health insurance, (universal) basic income or temporary unemployment benefits (bailing out individuals, not companies).

- “just in case” instead of “just in time” organizational models

- more cash reserves and less debt (for companies, households and governments)

- having a safety net of loyal, well-trained and adaptable full-time employees (rather than relying on free-lancers, consultants and gig workers)

Antifragile systems are not necessarily big government systems. People and governments tend to over-intervene on small things and under-intervene for large things. Governments should plan and provide buffers for extremes. This is especially true in areas with high uncertainty like climate change. Not the median value of expected temperature rise is so much important, rather than the ‘fat tail’ of improbable but potentially devastating temperature rises.

A way to make systems more antifragile is to make sure that those responsible have skin in the game:

“In the Hammurabi Code, if a house falls in and kills you, the architect is put to death”. Correspondingly, any company or bank that gets a bailout should expect its executives to be fired, and its shareholders diluted. “If the state helps you, then taxpayers own you.”

For companies, skin in the game means letting the process of creative disruption play out. If airlines used their cashflow in the good times to buy back shares instead of building reserves, why should they be bailed out? Governments could be made more responsible by linking salaries and incentives of politicians to debt levels, economic growth, poverty levels and well-being of the population.

Will covid-19 have a permanent impact and lead to more antifragile systems?

Memories are short. Additional expenses in hospital beds and strategic stocks of materials become harder to justify as memories fade. There will heightened attention for pandemic risks for some time now. But what about other systemic risks? The systemic risk of inflation and a corporate and government debt crisis is not high on the agenda now. Gone are calls for increased expenses in cybersecurity or counterterrorism. Attention for climate change mitigation has waned.

There is an increased focus on making supply chains more resilient, but this trend started before covid-19. This includes shortening them, reducing reliance on a few suppliers and increase investments in robotics. The nature of work is changing with more decentralization and distance work, but with a higher reliance on the internet. The covid-19 pandemic risks increasing the power of global corporations due to their better ability to raise free cash and lobbying powers.

What about education? Covid-19 has arguably spurred more innovation and investment in online learning than in the last 5 years. But will it last and will it make education systems more antifragile?

A basic problem in the organisation of education is low productivity increases compared to other sectors, a phenomenon referred to as Baumol’s Disease. A lack of relative productivity growth explains why salaries for educators struggle to keep up with those of other sectors and why pedagogical innovations such as differentiation, project-based learning and personalized learning struggle to find inroads.

The only plausible way to increase productivity in education is by online learning. By digitizing parts of the education process (explaining theory, showing examples, elaborating on topics, evaluation), time is freed for educators to focus on social support, individual learning support and supporting group activities. Making educators responsible for larger groups of learners allows for increasing their salaries.

Will covid-19 have a lasting influence on education? Many schools and teachers have experimented and developed skills with online learning. Many may continue developing instructional movies and online Q&A sessions. However, a real education reform would include moving away from year grades and fixed classes and a specialisation in teacher roles . Schools have a lot of autonomy in Flanders to experiment with online learning and the organisation of education. If covid-19 can result in lasting innovations in the organisation of education in our schools, it will have had a positive impact after all.

The Geography of Thought from Richard Nisbett shows that East Asia and the West have had different systems of thought, including perception, assumptions about the nature of the world, and thinking processes, for thousands of years. Ancient Greek philosophers were “analytic” — objects and people are separated from their environment, categorized, and reasoned about using logical rules. Psychological experiments show the same is true of ordinary Westerners today. Ancient Chinese philosophers and ordinary East Asians today share a “holistic” orientation — perceiving and thinking about objects in relation to their environments and reasoning dialectically (focusing on contradictions, change and relationships), trying to find the Middle Way between opposing propositions. Differences in thought stem from differences in social practices, with the West being individualistic and the East collectivist.

The Geography of Thought from Richard Nisbett shows that East Asia and the West have had different systems of thought, including perception, assumptions about the nature of the world, and thinking processes, for thousands of years. Ancient Greek philosophers were “analytic” — objects and people are separated from their environment, categorized, and reasoned about using logical rules. Psychological experiments show the same is true of ordinary Westerners today. Ancient Chinese philosophers and ordinary East Asians today share a “holistic” orientation — perceiving and thinking about objects in relation to their environments and reasoning dialectically (focusing on contradictions, change and relationships), trying to find the Middle Way between opposing propositions. Differences in thought stem from differences in social practices, with the West being individualistic and the East collectivist.

Exodus discusses the costs and benefits of mass migration. Paul Collier (author of “

Exodus discusses the costs and benefits of mass migration. Paul Collier (author of “

What is Information? Is it inseparably connected to our human condition? How will the exponentially growing flow of information affect our societies? How is the exploding amount of information affecting us as people, our societies, our democracies? When The Economist talks about

What is Information? Is it inseparably connected to our human condition? How will the exponentially growing flow of information affect our societies? How is the exploding amount of information affecting us as people, our societies, our democracies? When The Economist talks about  The core figure in the book is Claude Shannon. In 1948 he invented information theory by making a mathematical theory out of something that doesn’t seem mathematical. He was the first one to use the word ‘bit’ as a measure of information. Until then nobody would have though to measure information in units, like meters or kilograms. He showed how all human creations such as words, music and visual images are all related in the way that can be captured by bits. It’s amazing that this unifying idea of information that has transformed our societies was only conceptualized less than 70 years ago.

The core figure in the book is Claude Shannon. In 1948 he invented information theory by making a mathematical theory out of something that doesn’t seem mathematical. He was the first one to use the word ‘bit’ as a measure of information. Until then nobody would have though to measure information in units, like meters or kilograms. He showed how all human creations such as words, music and visual images are all related in the way that can be captured by bits. It’s amazing that this unifying idea of information that has transformed our societies was only conceptualized less than 70 years ago. Policy makers and the media have shown a remarkable preference for Randomized Controlled Trials or RCTs in recent times. After their breakthrough in medicine, they are increasingly hailed as a way to bring human sciences into the realm of ‘evidence’-based policy. RCTs are believed to be accurate, objective and independent of the expert knowledge that is so widely distrusted these days. Policy makers are attracted by the seemingly ideology-free and theory-free focus on ‘what works’ in the RCT discourse.

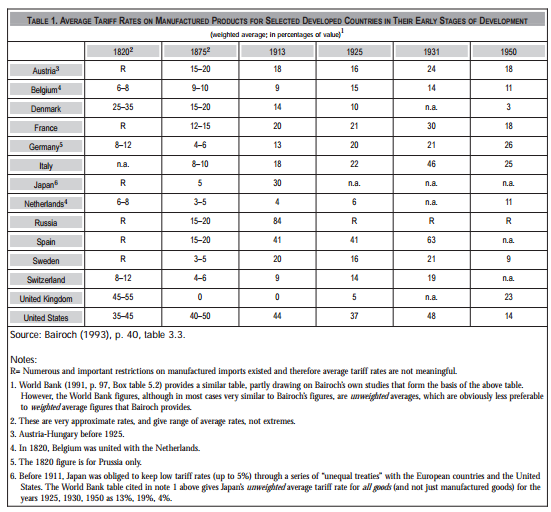

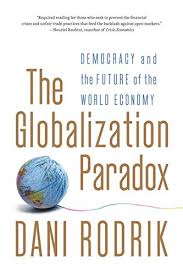

Policy makers and the media have shown a remarkable preference for Randomized Controlled Trials or RCTs in recent times. After their breakthrough in medicine, they are increasingly hailed as a way to bring human sciences into the realm of ‘evidence’-based policy. RCTs are believed to be accurate, objective and independent of the expert knowledge that is so widely distrusted these days. Policy makers are attracted by the seemingly ideology-free and theory-free focus on ‘what works’ in the RCT discourse. Developed countries stimulate developing countries to adopt the “good” institutions and “good” policies which will bring them economic growth and prosperity. These are promoted by institutions such as the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank. Recipes such as abolishing trade tariffs, an independent central bank and adhering to intellectual property rights feature high on their agendas.

Developed countries stimulate developing countries to adopt the “good” institutions and “good” policies which will bring them economic growth and prosperity. These are promoted by institutions such as the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank. Recipes such as abolishing trade tariffs, an independent central bank and adhering to intellectual property rights feature high on their agendas.