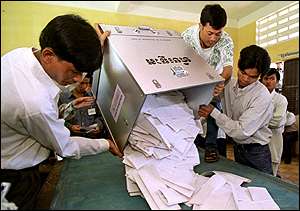

On July 28 parliamentary elections took place in Cambodia with 123 assembly seats up for grabs. Since the first, post-Khmer Rouge, UN-supervised elections in 1993, the Cambodia People’s Party (CPP) has steadily increased its grip on the country, securing a sound 90 seats and 2/3 majority in the previous elections in 2008, allowing it to form a government and make constitutional amendments without interference from the opposition. The CPP’s self-proclaimed strongman, Hun Sen, has been prime minister for 28 years.

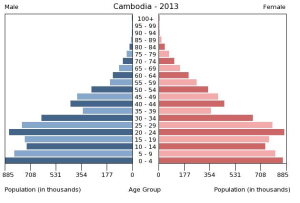

This time, things did not go completely as planned. The opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), galvanized by the return – under international pressure – from leader Sam Rainsy from self-imposed exile in France, obtained 55 seats (+23) according to preliminary results. Despite the fact that the CPP maintains a handsome majority in the National Assemby (68 seats on 120) there is little reason for cheering at the CPP headquarters. First, the CNRP obtained the majority in the capital Phnom Penh, and populous provinces such as Kampong Cham and Kandal. Due to limited resources, the CNRP didn’t campaign in some of the more remote provinces. Significantly, the opposition drew most support from the young and urban population. Cambodia has a very young population with a bulge between 20 and 29 years (see graph). Urbanisation has been fast in recent years, driven by growing export-oriented industry such as garment factories. The rise of social media, notably Facebook, seems to have been another help to the opposition, undermining the CPP’s dominance of the traditional media. Movies of supposedly indelible ink being washed off made rounds and stories of people unable to find their names in voter records quickly surfaced. The young seem less impressed by the traditional CPP recipe focusing on stability, economic growth and infrastructure. The CNRP has done well on pounding on the widespread land grabs, rising inequality and pervasive corruption.

source: CIA World Factbook

For now, the CNRP has rejected the result, claiming that widespread fraud has distorted and possibly reversed the result. It calls for an independent commission to investigate the results. Prime Minister Hun Sen has not yet formally commented on the result. The situation on the street is tense. The coming days may see mass demonstrations with risk on clashes and violence. Access to the area around the prime minister’s residence is blocked by armed forces. The opposition’s vitriolic anti-Vietnamese discourse raises concerns and fear with the numerous Vietnamese in Cambodia. People have started hoarding gasoline and instant noodles. Traffic is unusually calm and many shops are still closed.

The key seems to lie with the CPP’s reaction the coming days. They may remain calm and try weakening the opposition by contacting individual members of the opposition. However, they may also face an internal power struggle. Optimists hope the weakened CPP will feel the urge to reform and make concessions to the opposition. Anyway, Cambodia’s political landscape seems to have waken up, which is arguably a good thing. Good additional coverage on the elections’ aftermath from Sebastian Strangio (Asia Times) and The Economist.